The article investigates the evolution of tools to support supply chain finance from the perspective of the paradigm shift resulting from the succession of crises in recent years (pandemic, geopolitical crises, war) and the transition to greater sustainability of economic activities, proposing the basic elements of a new collaborative paradigm for the world of Supply Chain Finance.

Supply Chian Finance: the ongoing evolution

If we look at the current Supply Chain Finance context from a diachronic perspective, we can easily see that new requirements are being added to the two historical drivers of the development of this type of solution-the supplier's need for credit demobilization and the debtor's need to lengthen payment terms:

- the transition to sustainability, which equally impacts suppliers, customers and the financial system, but demands additional transmission and coordination efforts from the lead companies vis-à-vis their suppliers;

- the restructuring and relocation of many supply chains, to shelter themselves from the risks and uncertainties of an era of geopolitical disorder, which threatens the long trade routes of the global trade era.

The new needs may result in a qualitative leap from the historical drivers, in that they are no longer just the manifestation of precise and delimited financial needs, albeit opposed to each other, but fit within a broader matrix of needs, both from a qualitative and a quantitative point of view. In qualitative terms, because the financial component from an autonomous objective becomes a tool for the achievement of more complex goals, based on all-round sustainability objectives: environmental, social, economic, credit, etc. In quantitative terms, because the scope of the new requirements encompasses a potentially much broader range of suppliers than those traditionally involved in the development of SCF solutions with an exclusively financial purpose.

This circumstance defines a potential holistic approach to supply chain management, no longer based on the pursuit of specific sectoral objectives, but hinged on overall value growth for all components of the supply chain, through strategic management of the financial and credit levers that can guide business development. In this logic, financial objectives are no longer an end in themselves, but become instrumental to the overall goal of ensuring the sustainability and business continuity of the supply chain, sharing mechanisms, information and credit capacity between the strongest and most vulnerable components.

What does this mean in practice? It means that to manage the supply chain in the turbulent environment around us, we need to start thinking big. It means going beyond the immediate financial goal to think about customer-supplier financial relationship management tools focused on sustainability and supply chain stability. Tools not dedicated only to the most important suppliers, but at least potentially extended to all suppliers relevant to supply chain stability.

Supply Chain Finance: what new frontiers?

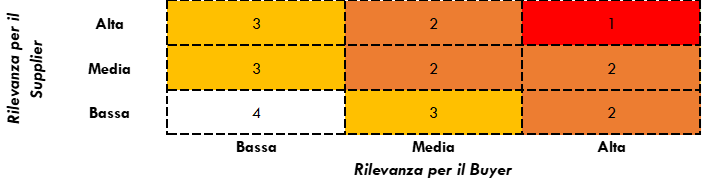

To decline this concept, let us try to imagine sounding out the supply chain at the end of which is our company. The relevance of individual suppliers is not just a function of purchasing size. We must also consider the quality of the relationship, the continuity and punctuality of the service, the replaceability of the supplier in the short or medium term, and the level of integration with our production processes. Geographical or logistical considerations may be relevant, rather than the impact on specific products and markets that may be very critical for us. Let us say that the result of this analysis phase is an index of the importance of the individual supplier to us. At this point, it is useful to ask how important we are to the supplier. The drivers are probably the same, but viewed from the supplier's perspective.

Combining the two indices, ideally reduced to a minimum metric dimension (high/medium/low importance) yields a supply chain segmentation that incorporates an index of priority in involvement in supply chain consolidation programs.

What these programs can consist of depends on the combination of goals we want to pursue as customers and supply chain leaders, and they can also be diversified by classes of suppliers.

A few examples of possible goals, again to keep it concrete.

- Introduce shared sustainability metrics on which to engage the supplier

- Measure the individual supplier's positioning against these metrics and, possibly, against the achievement of shared goals.

- Provide financial support to suppliers asked to support certain investments, e.g., to relocate activities, rather than certain quantitative or qualitative levels.

- Provide compensatory financial support to rebalance cash flow circulation in the supply chain.

- Directly or indirectly provide credit to support the start-up phases of certain production programs.

- Directly or indirectly provide liquidity to reduce the risk of supplier default.

- Expand procurement volumes to suppliers that have strict exposure limits, providing tools to reduce their risk.

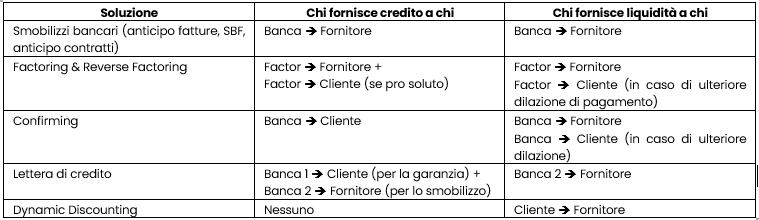

Financing the supply chain: today's tools

The instrumentation that Supply Chain Finance provides to achieve these objectives is, of course, a financial instrumentation, based on the use of two main levers: credit and cash. Credit is, first of all, what the supplier does to the customer in all cases where payment is deferred from the time of performance. To give credit to the customer means to advance (at least in part) costs and, therefore, to use one's liquidity to finance the customer's debt. The solutions offered by Supply Chain Finance tend to mitigate this type of situation, avoiding liquidity crises on the part of the supplier through the combined use of credit and liquidity levers provided by parties other than the supplier itself. The different classes of solutions are distinguished, essentially, according to the combination of levers they realize. The following table proposes a map of the main solutions, articulated through this key.

- Whenever credit relationship and liquidity relationship coincide we are moving within a traditional banking operating environment, with familiar rules and equally familiar technical and operational limitations: the bank/customer relationship is 1:1, we move within the bounds of the credit assessment made by the bank to the customer, the relationship facility follows the bank's compliance rules and uses its contractual and operational processes and instrumentation.

- When the two relationships do not coincide, the practical approach of operators is to multiply the underlying processes so that traditional linear (1:1) relationships can be replicated. This approach makes the implantation of these solutions (nonrecourse reverse factoring, confirming) particularly laborious, and even when banks equip themselves with digital tools to reduce the friction of the operational relationship with the customer (and their own internal operational costs), they are still custom tools, forcing firms to measure themselves against different (sic!) standards.

A corollary of these considerations is that the traditional instrumentation of Supply Chain Finance performs very well when it can be realised through operational models that adhere as closely as possible to customary patterns, while it falters somewhat when faced with the need - or even the demand - for different patterns, which it tries to solve through additive rather than subtractive processes: better to multiply activities according to known patterns than to consider using non-proprietary standardised processes.

This approach is perfectly legitimate, and even relatively effective, in all cases in which the customer is not interested in an active management of the financial relationship with its supplier, but it is not without its drawbacks when supply chain finance becomes an instrument of implementation of the customer's policies to build loyalty, strengthen and consolidate its supply chain. In this logic, the focus on the direct - and perhaps exclusive - relationship between the bank and the individual supplier becomes an obstacle and a factor of operational stickiness, just as the use of the bank's proprietary technicalities and procedures tends to become an implicit limitation with respect to the client's ability to pursue, and achieve, its own objectives.

The scenario that opens up in the new context, which sees a widening of the range of needs and the number of actors potentially involved in an active supply chain management perspective, questions the availability of adequate tools to support supply chain policies that are more articulated than traditional ones.

Supply Chain Finance: functions and limitations of market platforms

Beyond the obsession of some banks with the use of proprietary instrumentation, the supply chain finance market is populated, especially at the international level, by numerous entrepreneurial initiatives that have developed digital platforms that interpose themselves between the client and the other players in the system: banks and suppliers.

These platforms are based on integration to treasury systems rather than directly to corporate ERPs, and are therefore capable of standardising the extraction and processing of data from the client's system, without forcing it to adapt to the proprietary standards of each individual bank. It is therefore a matter of platforms that are fed directly by the customer's accounts, in accordance with the fundamental logic of supply chain finance, and not by the supplier. The latter is therefore a passive user, from the point of view of data feeding, but benefits from an active interface that enables him to carry out credit assignment operations, within the limits of the items fed by the customer.

To complete the system, the platform provider develops integrations to the proprietary systems of the affiliated banks, so that they can transfer to them information on the transactions that take place on the platform.

Some considerations on the different underlying business models and the practical consequences with respect to the functioning of the Supply Chain Finance programmes supported by these platforms.

- It is clear the value of simplification and standardisation that the platform approach guarantees to the customer with regard to the management of supply flows to the platform itself and also with regard to the guarantee of a uniform user interface to its suppliers.

- The business becomes more complicated when one looks at the contractual and operational relationship with the bank(s) involved. In this respect, there are at least two business models that can be found in the market: the first entails that the platform also centralises the financial aspect, usually through the establishment of a vehicle, which materially buys the suppliers' receivables and then resells them, within the framework of securitisation transactions. In this case, the platform acts as the organiser and manager of the entire transaction, which may involve numerous financial entities as final subscribers to the notes issued by the vehicle. The second model, on the other hand, involves the banks negotiating directly with the client, defining a portfolio of suppliers reserved for them, and directly managing all contractual formalisation and supplier onboarding activities, following their proprietary schemes.

- In the first case, the result is a single programme, the size of which is determined by the overall capacity of the Funders that will underwrite the notes. In the second case, there will be as many programmes as there are banks involved in the transaction. Standardisation and operational simplification are therefore effective only in the first case and at the price of substantial uniformity of the initiative.

Supply Chain Finance: the tools of the future. Thinking big

Thinking big. Is it just an illusion?

The real limitation of traditional and platform solutions is the difficulty for all operators to escape the mainstream scheme of traditional solutions, based on a 1:1 supplier/bank relationship, implanted using the bank's own processes and contracts. The mainstream scheme conditions the operators' approach and is based on the deterrent force of individual bank compliance functions, combined with the stickiness of any IT evolution process within the banking context.

This is not to say that there is no solution.

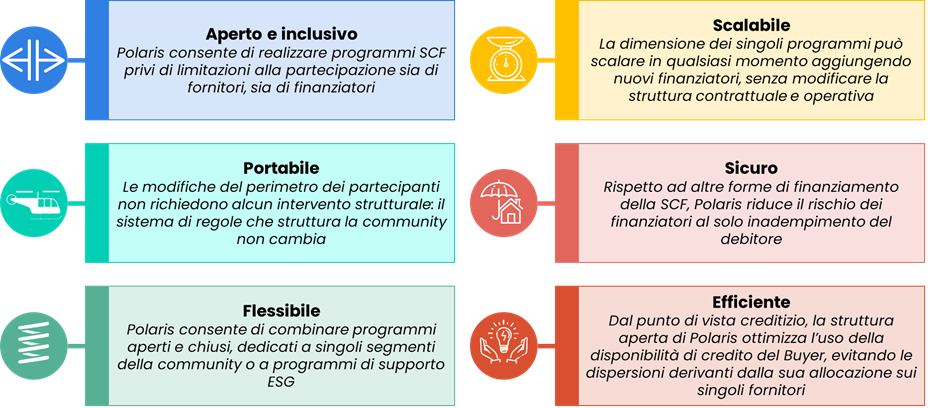

The solution is indeed trivial, but it does require that we think big, redesigning the division of labour and the structure of the relevant obligations in a logic of a market platform for supply chain finance and not a platform supporting the banks' reverse factoring operations.

In this logic, the platform is an IT infrastructure, certainly, but above all a contractual one, equipped with an autonomous manager whose mission is to ensure the functioning of the exchange system, the feeding and trading processes, guaranteeing the mutual reliance of the participants. This translates into a contractual and operational set-up that is autonomous from the customised ones of the individual banks, but nevertheless such as to ensure compliance with all relevant regulations..

Once the contractual and IT infrastructure has been separated from the actors in the system, there remain, on the one hand, all the IT integration issues that already constitute the main raison d'être of market platforms today, and on the other hand, the widest possible freedom to organise the exchange system, once again eschewing the traditional schemes of global assignment to a single banking or financial partner.

What we have briefly described is, in reality, a kind of regulated market (on a voluntary basis) for the commercial debt of large corporations. A market that is potentially open to every class of financial player, on the one hand, and almost every class of supplier, on the other. A market that allows the parent company to autonomously and flexibly manage its supplier support programmes, introducing the parameters and discriminants functional to its objectives.

The result is an open instrument to support the supply chain finance programmes of large companies, fed by them with verified and payable invoices, thus with no risk of dilution for the financiers. An instrument in which the participation of lenders is essential, but does not necessarily generate position or portfolio returns. An instrument that does not force suppliers to do anything, but merely allows them to turn their credit into liquidity when they need it. An instrument that optimises the credit leverage available to the customer, allowing it to be used by all the suppliers involved, without assigning rigid quotas to each of them. A tool that does not force replication of the implantation process if lenders change. A tool that defines a community of companies that cooperate, sharing processes and information, with the specific objective of improving the liquidity of the supply chain.

Such a tool is possible. In fact, it already exists.

Thinking big: Polaris

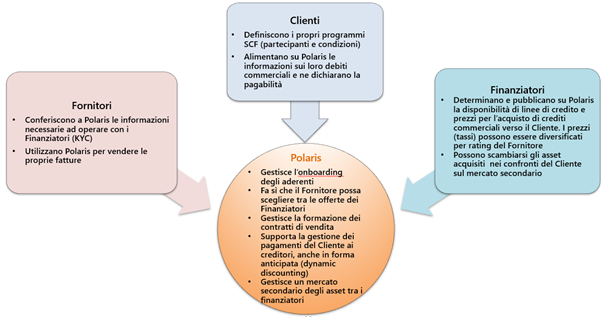

Polaris is the name of the Supply Chain Finance digital platform conceived and implemented by the TXT Group.

This is not the extemporaneous initiative of those who follow the fashions of the moment, but an initiative that starts from consolidated business skills, from a deep knowledge of the regulatory context, treasures the discussions developed over years of active participation in the Supply Chain Finance Observatory of the Politecnico di Milano and crosses the IT skills of the TXT Group. It is not a gamble, but the result of "thinking big" applied to the Supply Chain Finance business

Polaris proposes a new model of doing Supply Chain Finance, centred on the client company's interest in the financial soundness and sustainability of its supply chain as a prerequisite for the sustainability of its own business. With this clear objective in mind, the choice of tool is equally clear: an open tool, based on a service model that centralises onboarding and negotiation processes, developing an efficient division of labour between all players in the system.

The division of labour is combined with a series of technological and process innovations, all oriented towards simplifying the use of the service for all categories of users (Customers, Suppliers and Lenders), in a logic of optimising all the activities necessary for the market to function, overcoming the encrustations deriving from the practices of traditional products.

Within Polaris, Confirming, Reverse Factoring, Dynamic Discounting are just useless labels. Polaris allows Suppliers to transform their receivables into cash in advance in a potentially competitive environment and without incurring debt. This allows the customer to better manage its operational working capital, in collaboration (and not in opposition) with its suppliers and financial partners. The latter benefit from an ecosystem that reduces the risks and operational costs of their short-term investment in trade receivables.

The division of labour between users and the process innovation summarised in the figure above are the key to a product that defines a new horizon in Supply Chain Finance.